The gift of peer understanding: A qualitative study.

Title: The gift of peer understanding: A qualitative study of a suicide bereavement support group in Ireland and Denmark

Jean Morrissey 1; Agnes Higgins 1, Niels Buus 4,5, Lene Lauge Berring 2,4, Terry Connolly 6,

and Lisbeth Hybholt 2, 3,

- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, D02PN40 Dublin, Ireland; mo******@*cd.ie (J.M.) ah******@*cd.ie (A.H.)

- Psychiatric Research Unit, Psychiatry Region Zealand, 4200 Slagelse, Denmark; le**@*************nd.dk (L.L.B) and li**@*************nd.dk (L.H.)

- Research Unit, Mental Health Services East, Psychiatry Region Zealand; 4000 Roskilde, Denmark li**@*************nd.dk (L.H)

- Department of Regional Health Research, University of Southern Denmark, 5000 Odense, Denmark le**@*************nd.dk (L.L.B.) and ni********@****sh.edu (N.B)

- Monash Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Melbourne, VIC 3800, Australia; ni********@****sh.edu

- Friends of Suicide Loss (FOSL), D06T685 Dublin, Ireland; in**@**sl.ie

Correspondence: Jean Morrissey, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, 24 D’Olier St., Dublin 2, Ireland. Email: mo******@*cd.ie

Funding statement: The research received funding from Region Zealand Health Scientific Research Foundation, Denmark.

Authorship statement: All authors have contributed to the development of this manuscript. JM, AH and LH undertook data collection and analysis in addition to drafting the manuscript. NB, TC & LB contributed to the development of the manuscript.

Declaration of conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest with this research.

Ethical approval: This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faulty of Health Sciences, Trinity College Dublin. The Danish arm of the study received ethical approval from the Data Protection Agency and the regional research ethics committee.

Acknowledgements – the research team acknowledges and appreciates all those who shared their stories in Ireland and in Denmark.

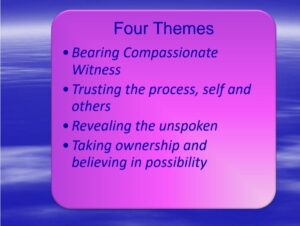

ABSTRACT: The experience of suicide bereavement has considerable impact on people, with an increased risk of adverse physical, mental, and social health outcomes, including increased risk of suicide and suicide attempt. There is a growing recognition of the power of peer support within all aspects of health, including suicide bereavement. While previous studies highlight the positive impact of peer support groups, there is a need for more studies on groups practices and processes, to develop greater insight into the helpful elements that may be distinctive to bereavement support groups for traumatic loss such as, suicide. This paper, drawn from a wider study, focusses on the interpersonal processes within peer suicide bereavement support groups. Using a qualitative descriptive design, focus groups and individual interviews were conducted online and face-to-face with a purposive sample of 27 participants in Ireland and in Denmark, who were bereaved by suicided and were attending peer bereavement support groups. Thematic analysis resulted in the development of four themes: ‘Bearing compassionate witness’, Trusting the process, self and others’, ‘Revealing the unspoken’, and ‘Taking ownership and believing in possibility’. Findings are reported in accordance with COREQ guidelines and suggest that the group provided a safe place where people felt and nurtured a deep emotional connection between themselves and others, a place where people trusted themselves and others to speak the unspoken and tell and re-tell their story without fear of consequence and a place where they learnt to process their loss and look to the future with hope. Mental health practitioners need to be aware of, and value suicide bereavement peer services as both an intervention to support people process loss and grief and a possible suicide prevention strategy, given the potential risk of suicide with bereaved families.

KEY WORDS: suicide, bereavement, peer support, group

Introduction

Suicide prevention is a significant public health priority of global concern. As a leading cause of death worldwide, it is estimated that over 703,000 people die by suicide each year and many more attempt suicide (WHO 2021). The experience of suicide bereavement has considerable impact on people, with an increased risk of adverse physical mental and social health outcomes (Spillane et al 2018; Erlangsen et al 2017), including increased risk of suicide and suicide attempt (Pitman et al 2014). A meta-analysis by Andriessen et al (2017) reported that approximately 1 in 20 people are impacted by suicide in the following year whereas 1 in 5 individuals will be impacted by a suicide during their lifetime. The interpersonal impact on those bereaved by suicide extends far beyond family members or those closely related to the person. It is estimated that for every suicide, approximately five or more close family members are affected and up to 135 individuals within the broader community (Cerel et al 2018). Other studies on people bereaved by suicide reported how the feelings of stigma make social interactions difficult, uncomfortable, and painful, which in turn, leads to withdrawal and self-isolation (Zavrou et al 2022; Entilli et al., 2021). Compared with other types of bereavement, people bereaved by suicide are at increased risk of experiencing problems such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), self-harm, dying by suicide themselves (Maple et al., 2016), alcohol use and relationships problems (O’Connell et al., 2022).

In recent years, there is a growing recognition within policy and practice literature of the power of peer support within all aspects of health, including mental health (White et al 2020). The inclusion of peer support within published international bereavement support guidelines (Support After Suicide Partnership and the National Bereavement Alliance 2019; Public Health England 2016; Scottish Government Health Directorate 2011) has also gained momentum. Those that advocate for peer support services, do so on the premise that people who have lived experiences can offer more authentic empathy and validation, as they can truly enter the lived world of the other (Watts & Higgins 2017).

Of the ten research studies included in Higgins et al’s (2022) review of peer-support interventions, six had a face-to-face peer-support group element (Ali & Lucock, 2020; Tosini & Fraccaro, 2020; Feigelman et al., 2011; Barlow et al. 2010; Feigalman & Feigalman et al. 2008; Hopmeyer & Werk 1994), the remaining four were online. Qualitative findings from these face-to-face interventions suggest that attending peer support groups increases people’s sense of connectedness as well as their self-worth by helping others. Participants also reported that the peer group helped them to process their grief, normalised their loss as well as offered the opportunity to memorialize the deceased. All of these had a positive impact on participants’ feelings of stigma and self-blame. However, a recent pre- and post-test study of people attending a suicide bereavement peer support group, reported that although there was a significant improvement in well-being and a reduction in grief reactions, at follow-up perceived stigma as measured by the Grief experience questionnaire did not improve (Griffin et al 2022).

While studies highlight the impact peer support groups have on people bereaved through suicide, authors have identified a need for more studies on groups practices and processes, to develop greater insight into the helpful elements that may be distinctive to bereavement support groups for traumatic loss such as, suicide (Higgins et al 2022; Bartone et al 2019). In a previous paper, we explored participants’ perspectives on peer-led support groups for people bereaved by suicide and identified how the peer support groups offered ‘alternative’, ‘transformative’ and ‘conflicted’ spaces for belonging and participating, which aided people recovery process (Reference inserted after review). However, our analyses indicated that rich parts of the dataset were not sufficiently addressed, hence this paper focuses in greater depth on the distinctive nature of the interpersonal processes within peer suicide bereavement support groups.

Design

The methodology for the study was qualitative descriptive (Colarafi & Evans 2016) involving focus groups and individual interviews. Individual interviews were offered to those participants who could not access the focus group. This design was selected as the preferred method to facilitate in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences from suicide bereavement peer support groups. The COREQ 32-item checklist (Tong et al., 2007) was used to support the drafting of this paper.

Recruitment and Sample

This study was conducted in Ireland and Denmark. Recruitment was based on purposive sampling of participants who met the inclusion criterion of being over the age of 18, bereaved by suicide for more than one year and were attending the Irish organization ‘Friends of Suicide Loss’ (FOSL) and the ‘National Association for the Bereaved Suicide’ (NABS) in Denmark. Prior to commencing data collection, both organizations were involved in circulating information about the study to their membership via a variety of methods (poster, online and verbal). Potential participants contacted the research team directly or gave permission to the respective organization to pass on their contact details. Detailed written and oral information about the aims of the study and inclusion criteria study were sent to all participants prior to consenting to the focus group/interview. Out of a total of 29 expressions of interest, 27 people, 13 in Ireland and 14 in Denmark were interviewed (Table 1). One person who initially agreed to attend the focus group cancelled due to sickness and another did not take up the offer to attend for unknown reasons.

Insert Table 1 Profile of Participants

Data collection

In Ireland two focus groups were conducted online on Microsoft Teams due to COVID-19 restrictions at the time of the study. Individual interviews were also conducted via telephone (approx. 60 min each) with two people who were unable to participate in the online focus groups. In Denmark, two face-to-face focus groups were conducted in private meeting rooms in a hotel. The length of the focus groups was between 120 and 150 min. The research team consisted of women and men who were experienced in qualitative methods and came from a variety of health backgrounds. All focus groups were facilitated by researchers (JM; AH; LH) who were from disciplinary backgrounds of mental health nursing, counselling and with extensive experience in qualitative research and sensitive interviewing. The researchers did not know the participants personally. All focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded with permission. Focus groups were guided by an interview schedule (Appendix 1) developed by the researchers in consultation with representatives from the two organizations FOSL and NABS and informed by literature. To ensure consistency in data collection the same schedule was used for both the individual and focus group interviews.

Focus groups in Denmark were conducted in Danish, and professional translators were used to translate the interview schedule and the selected quotations used in this article. Each focus group began with introductions and a brief outline by the moderators on the format of the group including information about safeguards to protect their confidentiality. All focus groups and interviews concluded with a thank you and reminder of the available supports. Participants were informed that they could review their interview transcript or their own statements from the focus group transcript if requested, but no participant took up the offer.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the Irish study was granted from the Research Ethics Committee of the University. The Danish arm of the study received ethical approval from the Data Protection Agency and the regional research ethics committee. Participants were assured of anonymity, and voluntary participation was emphasised through the study information. Written and verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Being mindful of participants’ well-being, a follow-up telephone call was made after the interviews. In accordance with data protection legislation, the sharing of raw data across national borders was not permitted. In writing up the quotes, care was taken to remove any information that may inadvertently identify the person who died or their family member.

Data Analysis

All focus groups and interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) Six phase Thematic Analysis Framework. Data analysis was conducted using word documents, independently by researchers (JM, AH and LH), who then discussed the coding process and interpretation of the data with the wider research team. The research team acted as critical colleagues and through a dialogic process, alternative perspectives explanations and biases were constantly explored, assisting all three researchers, to remain vigilant about how their assumptions might influence interpretation. The findings of this paper were presented nationally and internationally.

Results

Through the analyses, four themes were generated which emphasised the centrality of bearing compassionate witness to one’s own and others’ pain and trusting the process, self, and others, as well as, creating a context for revealing unspoken feelings of shame and guilt and gradually enabling participants to believe in and share more hopeful and restorative narratives.

Bearing compassionate witness

Participants reported that a key strength of being part of the peer support group was that people were “compassionate with each other” (P1, Den). Although sharing and witnessing grief was emotionally taxing and as expressed by one participant, “It’s a club none of us want to be in or don’t want anyone else to be in (P13, Irl), from the outset of joining the group, people felt understood and emotionally connected with others. They spoke of “feeling immediately connected” (P3, Irl), “sharing a certain language” (P11, Den), “a place where I feel I am not alone” (P9, Den) and “being relieved” (P7, Irl) at joining the group.

Although participants were acutely aware that each person’s experience of bereavement through suicide was unique, they spoke of how members bore compassionate witness to their pain, in ways that went beyond the need for words or explanations. Along with compassion and non-judgement having one’s pain witnessed helped bring the grief and suffering into reality and enabled the pain to become more bearable.

“There is such an understanding, and it is just okay to be. I think it is one of the extraordinary things the association – meeting others in the same situation– you do not need to feel into each other or think what she thinks about it? or is she afraid to say something to me? – it is hard to describe, but is an exceptional space” (P1, Den).

This unconditional listening enabled people to ‘release and let go, tell that story into what every detail you like’ (P1, Den). The fact that group members did not hold a normative bereavement script or roadmap of how each person should think feel or behave, enabled each person to unfold their story in their own way and at their own pace. This not only helped people to bond together in solidarity, but it communicated a depth of compassion for the pain each person was experiencing.

“Like people, they’re telling their story in the support group and they start crying, you know that’s quite natural” (P9, Irl).

Whether conveyed through voice tone, facial expression, body language, listening, or silence participants were supported to feel, express, and give witness to an array of emotions including intense pain, sadness, grief, despair, anger, loneliness, feelings of rejection as well as feelings of joy. Group members actively listened without judgement, resisting the need to interrogate, interpret or respond with superficial comforts. The positive feeling of being understood and accepted, offered people a sense of belonging and validation, which in turn broke their sense of being different and alone.

“I think we can all feel other’s pain, even though it’s different but yet it’s all the same, no matter what way suicide happened. So, I think as a group you know you’re listening to somebody else talk and tell their story and you can feel empathy, you know for them” (P8, Irl).

As people told and retold their story, they not only recounted the ‘event story’ of the death itself, but over time they connected with the ‘back story’ of the relationship with the loved one (Neimeyer 2014, p. 29; Neimeyer 2006). In addition, through listening to others unfold their story, participants bore witness to how their own and others’ emotions ebbed and flowed, learnt to experience emotions without self-judgment and contain the enormity of their feelings as they revisited their story.

“[…] listen to and listen to others telling their stories, then you find out that all the strange thoughts in your head are not entirely abnormal. Others have struggled with the same things; it’s not just me. I thought it was really just me that felt so weird. I thought it wasn’t normal. That I was going crazy or something. I think that helped me a lot” (P2, Den).

For many participants, feeling heard and understood, facilitated them to be able to tell and re-tell their stories in different ways and at different times. Equally, hearing other stories that had or had not resonance with one’s own story provided different perspectives which in turn prompted refection and challenged ways of thinking.

Trusting the process, self, and others

Trust was an essential mediator in the whole group process, it was the thing that enhanced disclosure, understanding and the relationships. Trust was about believing in the goodness of the other, believing that each group member would behave with beneficence and would not do anything intentionally to hurt the other. In the context of this study, it was about trusting that through compassionate witnessing each person could unfold their story and heal at their own pace, while the narrator at the same time trusted the listeners not to interrogate or judge. This continuous practice of not judging others in turn helped the participants to learn to trust themselves and to stop the self-judgement, which was very beneficial in releasing any guilt they may have had. Participants spoke of always feeling they could participate at a level that they were comfortable with, choosing to share things or not with their peers as they saw fit.

“I remember the first time I participated in the group, there were people who welcomed me and understood how much grief I carried. I felt embraced entirely …Someone understanding how massive a grief you carry. It meant the world to me… You enter a space where people talk and ask about it, you share a cup of coffee, and it is not wrong to talk about it” (P7, Den).

Witnessing others speak and being heard without judgement, created the underlying conditions for building greater trust, which in a cyclical like process enhanced people’s willingness to continue to express their thoughts and feelings. Knowing in advance that the deceased nor themselves would not be criticized or shamed made revisiting the story of the death feasible and bearable.

“The critical part of this group is the non-judgement, there’s no judgement there at all” (P5, Irl).

“Being able to go to the organisation and talk to someone who have been through the same ordeal, and where what I say is not construed as if I am wrong … So much happens when you talk to one another” (P4, Den).

While the participants anticipated and observed the impact of suicide on themselves and their peer members; unlike encounters with people outside whereby they felt they had to mind or protect people by not speaking about their experience. Participants also trusted and respected themselves and each other to have the necessary resources and skills to contain and manage the emotions expressed and with support find their own path in dealing with the daily challenges of living with grief.

“When you tell somebody the story (in social network) you do have to mind them , it’s not the same as saying someone died from cancer, so people find it difficult to hear and the others were saying you become aware of the impact on other people and you are trying not to make them uncomfortable and you don’t deal with your own piece, in the group you don’t get that, it is your space, your time” (P8, Irl).

Participants also trusted that people understood their needs and that those who were saying less than usual during a group, chose not to attend a session or took a break from the group, knew what was best for them. Hence, people did not feel pressurized to speak, attend every session or provide an explanation or justification to the group. Instead, they were affirmed for their engagement and welcomed back on their return without question or comment.

Revealing the unspoken

As a death by suicide is outside society’s conventions and cultural norms the feeling of being connected and belonging resonated deeply within people. This in turn helped participants to leave off what some called ‘shields’ or ‘masks’ (P11, Den). Gradually people arrived at a place where they shared what for many had been previously unspoken. For some this was about “feeling jealous of other who still have their siblings” (P4, Den). For others it was the guilt induced questioning of themselves. Questions that not only haunted their days and nights but resulted in them developing an internalized sense of shame. As one participant described “after you lose someone close, you start tearing yourself apart, all the things you should have done and didn’t do” (P6, Den). Many of these questions arose from the belief that ‘there are always warning signs’, which was particularly acute for those who had lost a child at a young age: “as a parent you are supposed to protect your children” (P5, Irl). Faced with the reality of being in a position wherein they could not influence the deceased behaviour, undermined their knowledge of the person’s distress, their relationship and confidence, as reflected by this participant:

“No, it [suicide] is different, you know because a person has actually, must have been thinking about it for a while, must have been, you don’t know what was going through their mind, why did he not come and talk to me” (P3, Irl).

Through sharing within the group people not only encountered compassion and non-judgement but came to the realization that although their feelings and stories were unique, the self-questioning that arose from the need to make sense or have a logical explanation for the suicide was universal.

“When somebody takes their own life it’s different. There are questions, questions why, why and people in the support group are asking the same questions. Why did that happen, why did I not see it, you know why, what was it, you blame yourself, did I do something wrong? And it’s universal in the support group. Everyone feels similar” (P12, Irl).

Gradually over the course of time, participants started to reframe and rethink the ‘shoulds’ and ‘coulds’ that had entrapped them in the cycle of rumination and learnt to construct a new restorative narrative, one where the internalised shame or taking responsibility for the death was no longer at the foreground.

Taking ownership and believing in possibility

Notwithstanding the severity of the impact of suicide on bereaved survivors, over time in the act of revealing and listening, people were supported to move from a focus on why the person died to understanding themselves. In one participant’s words it was about “taking ownership and dealing with the side of it that is you” (P2, Irl).

As people started to focus on the ‘I’ as opposed to the person who had died, they slowly began to believe in the possibility of a transition from the life at the time of the suicide to life after. They learnt how to tell their story but also how to ‘own’ their story and talk about how it affected them. By moving from the story of the deceased to the story of the bereaved, participants realised that their beloved deceased was part of their lives but not their whole life.

“You know for the first few years it is about the person and you’re not actually kind of thinking, you’re just basically speaking about them and not yourself. Whereas the group gives you the opportunity to talk about you and how you felt about it, not about what they went through and what led them to it, why they did it or whatever” (P13, Irl).

People spoke of changes such as returning to work, developing the ability to talk about the deceased with people outside the group, to developing hope and courage to carry on with life.

“It has encouraged me to believe that moving on from such a loss is possible… that you are able to love and be in the grief and still move on; there is a life afterwards” (P12, Den).

Witnessing such positive changes in themselves and others acted as points of hope and courage and showed that although sadness would always be present ‘getting better with it’ (P2, Irl) or “bring the load with you” (P5, Irl) and “learn to live and not just only exist” (P5, Den) was possible. As people took ownership, they also moved from not wanting to be part of the group to seeing it as a comfort, and a gift to each other. Some participants knowing the challenges they had encountered in finding a peer support group and valuing the help they received from the solidarity and the empathy of their peers felt compelled to reciprocate by supporting the development of other peer support groups for people who may not have access to a similar group.

Discussion

Our findings highlight that finding ‘a safe place where it is Ok to have a problem’ is just as important as finding a solution to a problem’ (Watts & Higgins 2017 p.82). In the context of this study, a consistent theme within each person’s story was that the group provided a safe place where it was OK not to be OK, a place where they could tell whatever aspect of their story they chose without fear of consequence and a place where they bore compassionate witness to their own and others’ pain and distress. The most important starting point for people was a feeling of relief at being understood not just at a cognitive level, but one where they felt there was a deep emotional embodied connection between themselves and another. This contrasts with what many people bereaved by suicide experience within the wider social network where people either avoid discussion, express sympathy, or empathy ‘for’ the person (Hybholt et al 2022), but do not understand the experience of bereavement through suicide in the embodied way that peers do. The absence of compassionate others to whom participants could relate their pain without having to be concerned about their distress or fearing being judged, was the motivating factor for people to enter the group. Like other studies, findings from this study reaffirm the power of the peer group to enhance peoples’ sense of connection, reduce feelings of isolation, support the reframing of feelings of blame and shame, as well as help people find hope for the future and begin to integrate their loss into their everyday lives (Bartone et al 2019; Fiegelman & Fiegelman 2008).

It is widely acknowledged that suicide bereaved experiences are exacerbated by feelings of guilt and self-doubt about what the bereaved could or should have done prior to the suicide. Indeed, Feigelman & Cerel (2020, p.1) comment that ‘it is almost axiomatic in the bereavement literature that suicide bereaved experience feeling of guilt and blameworthiness’. Participants in our study were no different, they recounted how prior to coming to the group they were trapped in a cycle of ‘what I should have done’ and in an attempt to protect others, in a cycle of silence around these feelings of shame and guilt. Given, that Feigelman & Cerel (2020) report a relationship between blameworthiness and grief difficulties (complicated grief, PTSD, depression) among people bereaved by suicide, finding a place where people can express feelings without feeling further guilt or shame is critical. While generic peer support groups can be effective for bereaved people, having specific peer support for people who are bereaved by suicide is important so that the distinctiveness of this experience, including feelings of guilt and shame, are heard, and accommodated with the sensitivity and the insight that comes from the lived experience of a suicide loss.

While all deaths challenge to some degree the taken for granted coherence of life, Rynearson (2012) suggest that when a death is relatively coherent with the survivor’s assumptive world, little active processing of its meaning may be required. However, when a death, like suicide challenges and invalidates the survivors’ self-narrative or story line, then considerable meaning reconstruction may be necessary. Findings from this study suggest that at the level of the individual, the process of telling and retelling of the narrative not only enabled restorative meaning making but supported people in their ongoing integration of the reality of the death into their wider life narrative. In addition, by listening to how other stories resonated with theirs, and by seeing other members of the group garner strength and courage, people were supported to manage the ebbs and flow of their emotions and engage with life and living outside the group. At a wider social level, in keeping with Riesman’s (1965) ‘helper principle’ as people realised that their own pain and healing efforts were of value to others and gained in self-belief and self-efficacy, they extended the hand of compassionate friendship to group members and to unknown others outside the group. Participants recounted how they not only supported members outside the group but supported the development of other peer-groups.

Within the therapeutic literature the term trust is frequently cited as a cornerstone of the therapeutic alliance (Tribe & Morrissey, 2021), yet a review of the literature suggests that as a concept it is seldom explored. Similarly, it is notable by its absence within the peer literature, yet this study suggests that trust formed the bedrock on which all the other processes within the group depended on. As an inherently reflexive and relational process, trust was as Rodrigues (2021, p.2) suggested ‘both an input and an output of communication’. The very act of trusting others to hear and receive one’s story with acceptance and compassion, in a cyclical manner fuelled further trust, which in turn nourished further disclosure and personal reflection. Trust also made revisiting the ‘event’ and the ‘relationship’ story feasible and bearable, which supports Rynearson’s (2006) assertion that having sufficient safety or trust is core to the restorative retelling of the narrative of loss.

Some previous studies report the potential for distress and re-traumatisation from being exposed to individuals’ narratives of loss (Bailey et al. 2017; Feigelman et al 2011; Feigelman & Feigelman, 2008). There is no doubt that people in our study found it challenging at times and painful to engage with their own and others’ stories. However, in this study the group appeared to have the ability to be present for each person and through their non-judgemental support and lack of normative expectations on how to feel, be or act they created a compassionate context where people were held and nurtured in their distress. There is also no doubt that the flexibility within the group that allowed people to proceed at their own pace as well as the autonomy to leave and re-join the group enabled people the feel less trapped within the intensity of their own and others’ grief. The flexibility of knowing one can leave without being questioned paradoxically may help people to stay.

While the findings from this study highlight important interpersonal practices and outcomes that are specific to people bereaved by suicide, the study has some limitations. Participants represented a small number of those bereaved by suicide in two different cultural contexts, thus findings may not be transferable to all peer suicide support groups, especially those that may be facilitated by professionals, or by someone without the lived experience of a death by suicide of a family member. As the sample was self-selected, with men and people from diverse minority background being underrepresented findings may also be biased. While collecting data through focused groups may help to hear diversity of opinion, social desirability may have hindered people expressing the challenges of being with and befriending each other without judgement or expectation. Finally, while the absence of no new information in the data indicated that data saturation was reached in relation to interpersonal processes, there is always the potential that had the researchers continued to recruit, new processes may have been identified.

Relevance for clinical practice

Mental health practitioners are frequently engaging with family members who are bereaved by suicide, yet studies suggest that they do not always provide information on bereavement peer support service to families (Farzana & Lucock 2020). Finding from this study not only points to the need for mental health practitioners to be aware of suicide bereavement peer services, so they can provide information to family members, but they need to value peer group not just as an intervention to support people process loss and grief but as a possible suicide prevention strategy, given the potential risk of suicide with bereaved families. Findings from this study also provide practitioners with insights that are significant to their helping relationships, such as the uniqueness of each person’s experience, the benefits of being given an opportunity to retell and explore the meaning of one’s story, as well as the power of listening without normative judgements.

Conclusion

Bereavement through suicide is complex and traumatic, with the potential for both disfranchised (Doka, 1999) and complicated grief. While previous studies suggest that peer suicide bereavement support groups through the universality of a shared experience are beneficial, this study extends our understanding of the reciprocity of the interpersonal practices that occur with peer-led suicide bereavement support groups and how these practices accommodate the distinctive nature of suicide bereavement. The process identified can also offer something of value to mental health practitioners and to those tasked with the ongoing development of suicide bereavement peer support groups.

Phone: +353 ***********76

Primary Email: fo******@***il.com

Secondary Email: in**@**sl.ie

Address: Tennant Hall, Christ Church, Rathgar, Dublin 6, D06CF63

Charity No: 20205573

© Copyright 2018 Friends of Suicide Loss

Developed by Kickstart Graphics